Clara Breed Civil Liberties Lecture

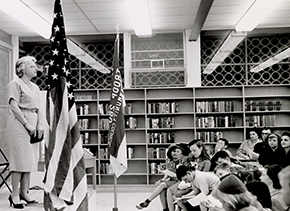

The Clara Breed Civil Liberties Lecture honors Miss Breed's triple legacy of service, decency and advocacy on behalf of Japanese Americans wrongly imprisoned in concentration camps by the federal government during World War II.

2024 Speaker | Dr. Stan Rodriguez

Tuesday, March 26, 2024 • Central Library, Neil Morgan Auditorium

6 p.m. doors open | 6:30 p.m. program starts

Registration is not required but encouraged. Click here to register for this free event.

Dr. Stan Rodriguez, educator and President of Kumeyaay Community College, delivers the 3rd Annual Clara Breed Civil Liberties Lecture.

Past Lectures

2023 Speaker | Shereen Marisol Meraji

Award-winning journalist, educator and UC Berkeley professor Shereen Marisol Meraji delivers the 2nd Annual Clara Breed Civil Liberties Lecture.

2021 Speaker | Renee Tajima-Peña

Oscar-nominated independent filmmaker and distinguished UCLA Professor of Asian American Studies, Director of the Center for EthnoCommunications and holder of the Alumni and Friends of Japanese American Ancestry Endowed Chair.

Quick links:

About the Project

In 2021, the San Diego Public Library reflected on Japanese American experiences during and after World War II by exploring themes of social justice, activism and the power of the written word. The library hosted a series of programs and events to raise awareness and encourage discussion of historical and contemporary issues faced by marginalized voices, especially within the Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) community.

As Japanese immigration to the United States started to increase in the late 19th century, Japanese Americans became targets of hostile discrimination. And as anti-Japanese sentiments gained momentum in the western United States, federal and state legislation prohibited Japanese and other Asian immigrants from experiencing social rights and becoming U.S. citizens. As hostilities toward the AAPI community continued to increase in the years leading up to World War II, the U.S. government conducted extensive surveillance of Japanese communities, ultimately producing “custodial detention lists” that were used to incarcerate “enemy aliens” following the attack on Pearl Harbor. President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942, which authorized the mass, forced relocation and incarceration of Japanese Americans in concentration camps known as “assembly centers.”

The library’s Rebellious Miss Breed also underscored the remarkable activism of Clara Breed, a San Diego Public Librarian, as she advocated on behalf of Japanese American children during and after wartime. The young library patrons, who were incarcerated in “internment camps” throughout the United States, exchanged letters, packages and books with Miss Breed. These exchanges provided significant lifelines and consolation for the several thousand San Diego residents of Japanese descent who were incarcerated across the United States.

A note about terminology: The San Diego Public Library is using terminology recommended by Densho, a nonprofit dedicated to preserving and sharing the history of the WWII incarceration of Japanese Americans, in order to use words that more accurately represent history. To learn more, visit Densho at https://densho.org/terminology/

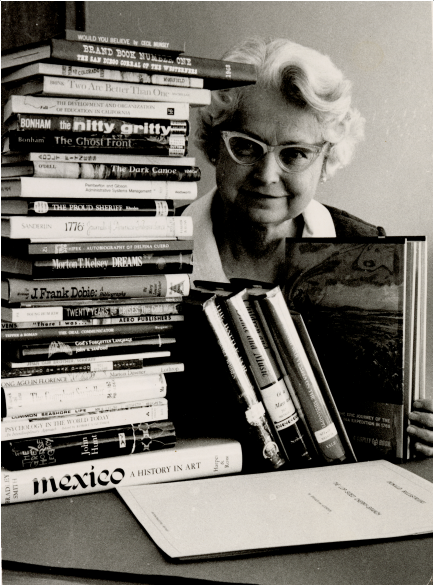

About Clara Breed

Clara Breed (1909-1994)

Miss Breed letter to Tetsuzo Hirasaki ![]() View letter

View letter

“Among the letters Miss Breed wrote to the incarcerated San Diego youths, the only surviving one is written to Tetsuzo Hirasaki who was the oldest. Written on American Library Association letterhead, it has no date and the envelop has no address. It is thought Miss Breed took the letter with her to the Santa Fe Depot train station on April 7, 1942, as Japanese Americans were being rounded up onto trains to remote concentration camps, and gave it to Tetsuzo.”

- Joanne Oppenheim, Dear Miss Breed: True Stories of the Japanese American Incarceration During World War II and a Librarian Who Made a Difference (Scholastic, 2006)

- "Clara Breed," Densho Encyclopedia

- "Clara Breed Collection," Japanese American National Museum

- https://postoninterneeobituaries.blogspot.com/2011/11/breed-miss-clara-estelle-1906-1994.html

Exhibitions

Call to Serve: Clara E. Breed & the Japanese American Incarceration & the WW-II Japanese American Incarceration Camp Replica was on view from September 18, 2021 to January 30, 2022 at the Central Library’s Art Gallery and Lobby. For information about the exhibitions, please visit On View: Art and Culture Exhibitions.

Call to Serve: Clara E. Breed & the Japanese American Incarceration & the WW-II Japanese American Incarceration Camp Replica was on view from September 18, 2021 to January 30, 2022 at the Central Library’s Art Gallery and Lobby. For information about the exhibitions, please visit On View: Art and Culture Exhibitions.

Virtual Tour

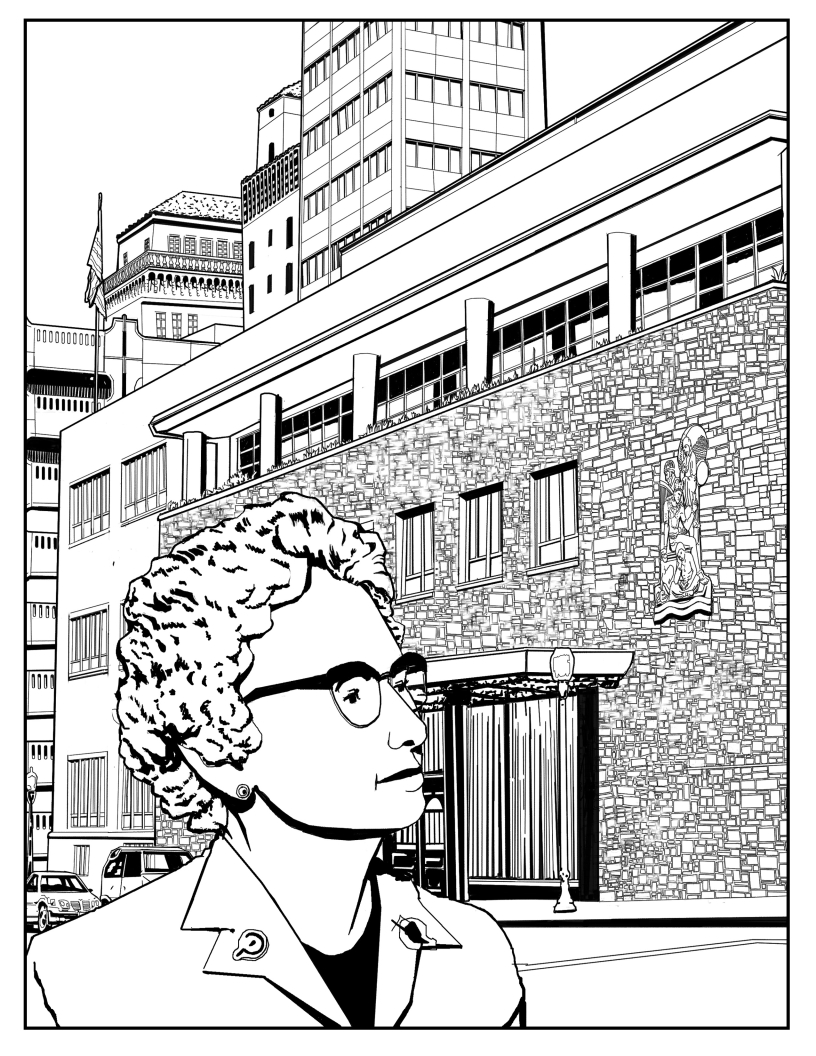

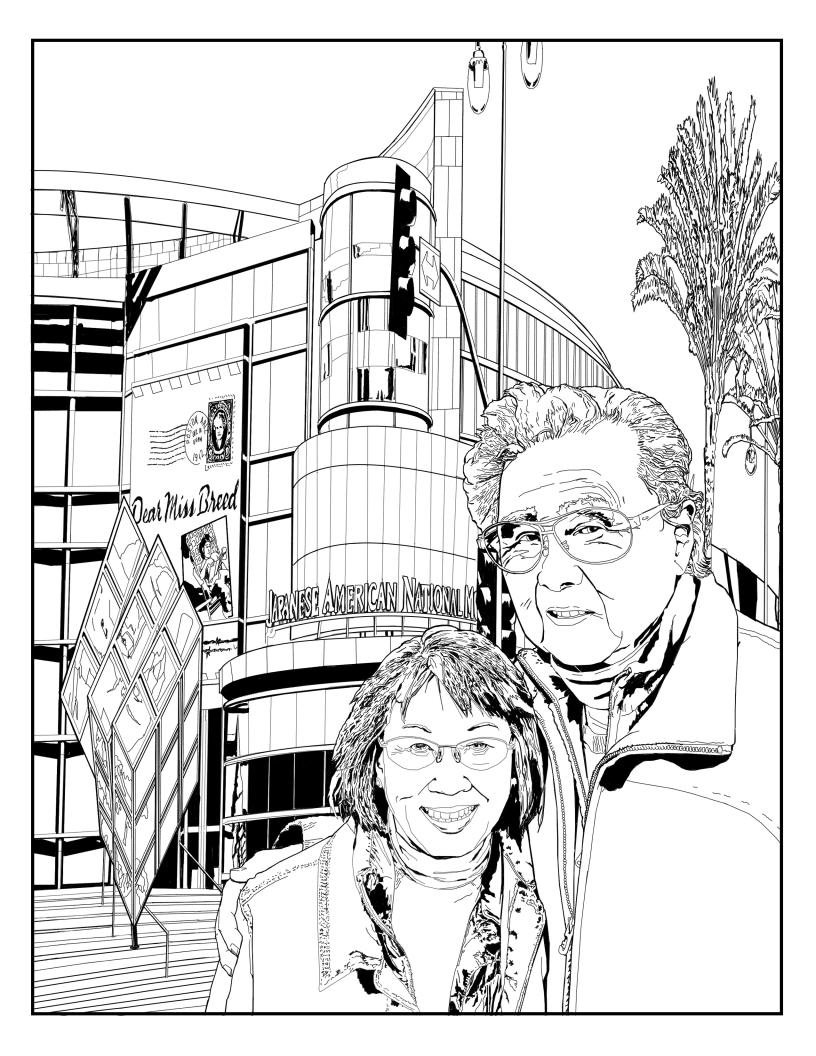

Coloring Pages

Download and enjoy these pages. Coloring pages #2 and #3 were created by the Los Angeles Public Library's Octavia Lab in celebration of heroes in California. Courtesy of Los Angeles Public Library.

Videos

Kamishibai Videos

Program Videos

Japanese American Incarceration

A short introduction to the history of the exclusion and incarceration of Japanese Americans during WWII.

Immigration and prewar prejudice

From 1885 to 1924, approximately 200,000 Japanese immigrated to Hawaii and 180,000 Japanese immigrated to the mainland United States. Over time, this first generation (Issei) built a vibrant community, raising families, starting churches, and forming social and business organizations. Their success met with prejudice and an anti-Japanese movement. Discriminatory laws prevented Issei from becoming naturalized United States citizens. They were barred from owning land, marrying whites and sending their children to schools attended by whites. Congress passed the Immigration Act of 1924 barring any further immigration from Japan.

The second generation (Nisei) also faced discrimination. Even though they were born in the U.S., spoke English like other Americans and often did well in school, these U.S. citizens of Japanese ancestry faced discrimination in employment, housing, public accommodations (restaurants, stores, hotels, swimming pools, etc.) and social and civic activities.

Arrest of community leaders

On December 7, 1941, Japan attacked U.S. military bases in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. More than 3,500 servicemen were killed or wounded. In the hours following the attack, the FBI arrested over 1,200 Japanese immigrant (Issei) men: businessmen, Buddhist priests, Japanese language teachers, and other community leaders.

More than 5,500 Issei men were eventually picked up and held as potential threats to national security. Most of these men were taken first to Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) detention stations and then to Department of Justice (DOJ) internment camps to undergo hearings. Officially, these internment cases were given individual legal review, but in practice, the majority of issei were imprisoned without evidence that they posed any threat to national security. Internees were not allowed legal representation. Approximately 1,700 were "released" to War Relocation Authority (WRA) incarceration camps after these hearings, but most were transferred to U.S. Army internment camps.

Mass removal of U.S. citizens

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which authorized military commanders to designate military areas from which any person could be excluded. Congress supported the Executive Order by authorizing a prison term and fine for a civilian convicted of violating the military order. General John L. DeWitt, Western Defense Command, then issued over 100 military orders that only applied to civilians of Japanese ancestry living in the West Coast states. Thus, the President and Congress authorized the removal and incarceration of over 110,000 people based solely on race without evidence of wrongdoing, charges or hearings. More than two-thirds of those incarcerated were U.S. citizens.

Ironically, over 150,000 people of Japanese ancestry in Hawaii were not removed or incarcerated. General Delos Emmons, who became commanding general in Hawaii shortly after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, treated the Issei and Nisei as loyal to the United States. Although there were many false stories of Japanese American spies, General Emmons repeatedly rejected anti-Japanese pleas to remove persons of Japanese ancestry from Hawaii. He knew there was no evidence of Japanese American espionage or sabotage. In fact, during World War II, no Japanese American in the U.S., Hawaii or Alaska, citizen or immigrant, was ever convicted of espionage or sabotage.

Dispersal to detention sites throughout the United States

The general public, through books, movies, and school lessons, is most familiar with the ten WRA incarceration camps such as Manzanar. The full extent of the imprisonment, however, included more than fifty-nine other government facilities: temporary "assembly centers," immigration detention stations, federal prisons, and internment camps. Italian and German immigrants, Alaskan natives, Japanese Latin Americans, and Japanese Hawaiians were also sent to live at these sites.

Which detention facility a person entered depended on several factors, including citizenship, perceived level of threat, geography, degree of cooperation or protest, and sheer chance. For the most part, the DOJ and U.S. Army camps interned first-generation (issei) men who were arrested by the FBI, while the WRA camps incarcerated both U.S. citizens and immigrants affected by the exclusion order.

Some leave camps, 'disloyals' transferred to Tule Lake

As early as April 1942, even before incarcerees were transferred from the temporary "assembly centers" to incarceration camps, the WRA recognized that Japanese Americans eventually would have to reenter society. Thus, the WRA enacted a policy of granting short-term or indefinite leave for college or work to Japanese Americans who were U.S. citizens (nisei) and who could find sponsors. Additionally, thousands of nisei men enlisted in the military and served in combat.

To help administer the military draft and work release program, the U.S. Army and the WRA produced "loyalty questionnaires" for all WRA incarcerees seventeen years of age and older. The questionnaires contained two questions that caused confusion and controversy for incarcerees. Despite serious problems with the wording and meaning of the questions, government officials and others generally considered those who answered "no" to these two questions to be "disloyal" to the United States, and they were transferred to the Tule Lake incarceration camp which was designated a segregation camp. "Yes" answers to these questions made incarcerees eligible for service in the U.S. Army, and some became eligible for release and resettlement in areas outside of the West Coast exclusion zones.

Government ends West Coast exclusion

In December 1944 the Supreme Court ruled in the case brought by Mitsuye Endo that a loyal U.S. citizen could not be held in a WRA incarceration camp against her will. While the case was being heard, federal officials recognized that the continuing incarceration was not legally defensible and began preparations to close the incarceration camps. In addition to the closing of the camps, the exclusion orders were rescinded and persons of Japanese ancestry were allowed to return to the West Coast. On March 20, 1946, the last WRA incarceration camp, Tule Lake, was closed. The DOJ internment camps remained open longer. The last internment camp to close was Crystal City in January 1948.

Upon release, the majority of those who had been incarcerated were given only $25 and one-way transportation. The freed Japanese Americans returned to discover many of their homes and farms had been vandalized and their belongings stolen. Even Nisei veterans returning home in their uniforms from combat duty endured racist insults. Starting over was especially hard for the Issei, who were entering their senior years with little to show for a lifetime of work.

Admission of wrongdoing, apology from government

In the late 1960s community activists started a movement to petition the government to look into potential government wrongdoings. Classified information was uncovered that showed the exclusion order and incarceration were based on racism and falsehoods. In February of 1980, Congress passed an act forming the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC). This commission conducted hearings in ten cities, heard testimonies from over 750 witnesses, and examined over 10,000 documents. In 1983, the CWRIC issued its report that concluded that military necessity was not the cause of the mass imprisonment. Rather, "...the broad historical causes which shaped these decisions were race prejudice, war hysteria and a failure of political leadership."

Acting upon the recommendations of the commission, Congress passed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 and President Reagan signed it into law. This law required payment and apology to survivors of the incarceration caused by Executive Order 9066. Two years later, President George Bush presented the first apologies, along with payments of $20,000 each to the oldest survivors.

Source:https://encyclopedia.densho.org/history/

© Densho 2021. The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. Where indicated, images and other primary source materials may be subject to use restrictions by their respectiverights holders.

Acknowledgements & Dedication

The San Diego Public Library wishes to thank the many partners, scholars, and community members who have contributed to The Rebellious Miss Breed: San Diego Public Library and the Japanese American Incarceration.Dedication to Survivors

The Rebellious Miss Breed: San Diego Public Library and the Japanese American Incarceration is dedicated to the people and survivors impacted by Executive Order 9066 and to their families and descendants. We wish to thank all the Japanese Americans featured in the exhibition Call to Serve: Clara E. Breed and the Japanese American Incarceration and in the performances by the School of Creative and Performing Arts and Write Out Loud. Finally, we wish to dedicate this project to Elizabeth Kikuchi Yamada, for her donation of Miss Breed's letters to the Japanese American National Museum, so future generations may be educated of this chapter in U.S. history and prevent such betrayal and injustice from ever happening again. Click here

Scholars, Activists, and Authors

- Daniel James Brown, author of Facing the Mountain: A True Story of Japanese American Heroes in World War II

- Cynthia Grady, author of Write To Me

- Susan Hasegawa, Professor of History at San Diego City College, and author of Japanese Americans in San Diego

- Kristen Hayashi, Director of Collections Management & Access and Curator, Japanese American National Museum

- Brian Hu, Artistic Director of the San Diego Asian Film Festival and SDSU Professor of the School of Theatre, Television, and Film

- Peter Irons, Legal Scholar & Professor Emeritus, Political Science, UC San Diego

- Michael Kurima, Co-President of the Japanese American Citizens League, San Diego Chapter

- David Loy, Legal Director, ACLU of San Diego & Imperial Counties

- Joanne Oppenheim, author of Dear Miss Breed

- Linda Salem, Interim Head of Collections, Children's Literature, Comparative Literature, and Education Librarian, Curator, Edward Gorey Personal Library, San Diego State University

- Bradford Pearson, author of The Eagles of Heart Mountain: A True Story of Football, Incarceration, and Resistance in World War II America

- Ted Shigematsu, author of The Cracks in the Life of Mike Anami

- Renee Tajima-Peña, Oscar-nominated independent filmmaker and distinguished UCLA Professor of Asian American Studies, Director of the Center for EthnoCommunications and holder of the Alumni and Friends of Japanese American Ancestry Endowed Chair

Community Partners

- American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) San Diego

- Friends of the San Diego Central Library

- Fresno County Public Library

- Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), San Diego Chapter

- Japanese American Historical Society of San Diego

- Japanese American National Museum

- Pacific Arts Movement

- San Diego Public Library Foundation

- San Diego State University

- School of Creative and Performing Arts (SCPA)

- Write Out Loud